Average DIY Investor Underperforms the Market: Here are 6 Reasons Why

There have been a number of studies that highlight how a retail do-it-yourself (DIY) investor consistently underperforms the market. Many have taken to managing their own portfolios either because of a bad experience with a previous money manager, mistrust of ‘financial advisors’, a confusing term often associated with an insurance salesman, mutual fund salesman, annuity salesman, money manager, financial planner, portfolio manager, etc. Or they may feel they are smart enough AND have enough time on their hands to manager their own money better than anyone else could. The data confirms that they can’t!

One of the most well-known studies on investor behavior and performance is conducted by Dalbar in their Qualitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, which is completed annually. Dalbar uses data from the Investment Company Institute, Standard & Poors, Bloomberg Barclays Indices, and proprietary sources to compare mutual fund investor returns to an appropriate set of benchmarks. The ‘average investor’ is defined by the behavior evident in mutual fund sales, redemptions, and exchanges. It does not apply to investors that buy individual securities as this activity would be much harder to measure – although I suspect it would be similar, if not worse.

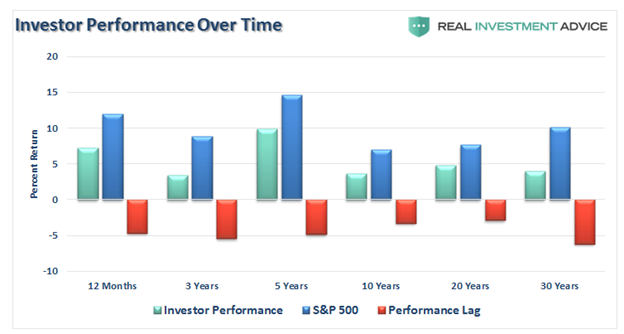

The chart below shows retail DIY investor performance relative to the S&P 500. It doesn’t matter what period we analyze, the results are the same – average investors have underperformed a buy and hold S&P 500 strategy – sometimes by a considerable margin. So much for not wanting to pay an advisor a fee for their services. With an annualized underperformance of more than 5%, some average investors are better off being less active – or hiring an advisor.

There could be many reasons why the average retail investor underperforms a simple buy-and-hold strategy,y but I will focus on just a few that I come across with uncomfortable regularity.

DIY Investor Psychology

Many DIY investors have a problem with timing. The problem is they think they are great market timers. Instead of buying low and selling high, however, they end up selling low and buying high. The process usually looks like this: The market starts declining and investors hold on to their positions thinking they would sell once the market recovers. (Selling a losing position will be like admitting defeat) As the market continues to decline, a panic starts to set in and the media paints a picture of a terrifying situation. As some investors start to sell (most institutional investors already sold), prices continue their downward trend causing more panic and eventually leading to even the staunchest of investors to sell – at the bottom.

Then, the institutional money realizes we’ve reached capitulation and figures out that even if the market may not be at rock-bottom, it’s cheap enough that it can start buying in again. Meanwhile, retail investors are licking their wounds, avoiding their brokerage statements, and still listening to ‘bad’ news not realizing that the bad news is now old news. Institutional money, however, is figuring out what is going to happen in the future, and although their crystal ball is no better than anyone else’s, they realize that things are getting better, and that it will eventually cause stock prices to recover. By the time the retail investor starts investing again, however, they’ve missed a considerable recovery in the market.

All or Nothing

The other factor that contributes to DIY investor underperformance can be captured by the often stated ‘getting in or out of the market’ comment, which implies that many investors are either completely invested or completely in cash at any given moment in time. This is an oversimplification but again implies that the average investor can figure out the exact moment when they should be getting in and getting out of the market. A more prudent strategy would be to gradually increase investments as the climate becomes benign and opportunities are presented, while gradually decreasing exposure as risks rise or the economic climate gets murky.

I like to compare managing a portfolio to driving on a long road trip. When the weather is clear and there is little traffic, we can speed up and drive a bit faster than we otherwise might. But a light rain may cause us to slow down a bit and be more cautious, while a torrential downpour might lead to even further reducing our speed. Add a bit of traffic (noise, risk, etc.) and you might slow down even further. But only if the storm is bad enough to reduce visibility to zero do we consider completely pulling over to the side of the road. Yet when it comes to investing, we move to the side of the road too often. This is what average investors do when they decide to reduce risk – they pull out of the market instead of just slowing down by reducing some exposure or adjusting their positions.

Lack of Strategy

As an investment strategist and portfolio analyst, I’ve seen a number of portfolios that are a collection of great individual ideas but that do not have a coherent strategy. It would be comparable to having a pantry full of tasty ingredients, together which would not make anything taste remotely edible. Proper money management starts with developing a strategy for how you should manage your portfolio – a recipe of sorts. Will you be aggressive or conservative? Are you seeking income or growth? How much risk are you willing and able to take? What is the time horizon you are considering for these investments? All of these factors and more will dictate how your portfolio should be managed and what specific positions you should be investing in and in what amounts. Just like you need to know what you are cooking in order to figure out which ingredients you will need and how much you will need of each.

Lack of Process

The lack of an investment strategy typically means there is no defined investment process in place either. An investment process is critical for money managers to measure and optimize their performance. When I’m conducting due diligence on a money manager, performance is important, but I spend more time analyzing their process. Performance can be luck unless it is repeatable and it’s the process that makes performance repeatable.

A process might include some or all of the following criteria:

- The universe of investments being considered (i.e. small cap growth stocks)

- The framework for analyzing a potential investment

- The criteria that each investment must meet (i.e. revenue growth, increasing margins, market share %, etc.)

- A timeline for reviewing and updating current holdings

- Analysis of how the holdings in the portfolio interact with each other

- Factors determining position size and process of increasing or decreasing positions

- Limitations on position size

- Limitations on sector or industry exposure

- Criteria for selling a position

All professional money managers likely have a disciplined process in place that guides their decision-making. The process can be adapted and improved as needed but the important thing is that there is a process in place. A DIY investor, on the other hand, is likely to not have a process at all. They are more likely to have a collection of individual ideas and no way to explain how they came together or why they are still in the portfolio.

Lack of Discipline

Even investors that have outlined their investment strategy and formalized an investment process oftentimes fall short when it comes to maintaining discipline. Too often exceptions are made because ‘this situation is different’ or an idea came from a successful investor friend. One exception might be OK, but if they become the norm, either the process is irrelevant or needs to be adjusted to reflect relevant investment criteria. It’s OK to adjust a process as needed to make it better, but when exceptions rule, underperformance will certainly follow. For example, if an investor has a rule not to invest in companies with a PE ratio above 24, a company with a PE ratio of 24.1 does NOT qualify. It should not be included in the portfolio. If it is, and these exceptions become the norm, then the investor needs to consider changing that criteria.

Concentration

By investing in a well-diversified index fund like SPY, an investor has diversification across 500 stocks. If any one goes to zero (possible but unlikely), it would result in a loss of just $2,000 on a $1M portfolio. But most investors might be concentrated in just 25-30 individual stocks. This is a reasonable number in that an individual investor probably can’t adequately follow more than this number of stocks – but it is still not adequate diversification in some cases. If one of these stocks goes to zero, the loss is $40,000!!

Conclusion

If professional money managers can’t outperform an index over long periods of time, why would a retail investor, even an extremely intelligent one, outperform? They wouldn’t. Combine several behavioral biases that retail investors are unaware of, a lack of strategy and process, a lack of discipline, and poor portfolio management that results in too much concentration or knee-jerk reactions, then the only thing left for an investor to rely on for outperformance is luck.

Can it happen? Yes, just like you can go to Vegas for a weekend and leave a winner. But go back on several occasions thinking you will have the same results and you might lose your shirt, or worse, your retirement dreams. After all, where do you think the money to build those beautiful hotels came from? If you want to gamble, go to Vegas, but if you are going to join the ranks of DIY investors learn the proper way to manage your portfolio, not just randomly pick stocks – or find yourself a trustworthy advisor. They might not always be right, but at least they will be objective.