Cash is Not King When It Comes to Investing

There’s a saying that Cash is King. A reference to the fact that Cash is accepted everywhere, it’s tangible, and it doesn’t rely on behind-the-scenes technology to transfer from one individual to another. It also requires the cash to actually be exchanged, whereby one person hands the money over to someone else. It’s not an electronic transaction where you can expect to receive the funds later based on the trust we have given companies like Visa and Mastercard, or the financial institutions that make up the banking system. Unless the cash is counterfeit, a person receiving cash knows that what they are receiving is legitimate and worth what it’s worth.

Cash is also nice to have when an investment opportunity arises, such as the case in 2008 when markets declined up to 50% before recovering, or in the current environment, where the S&P 500 dropped 34% before reversing course and recouping some of those losses. Having cash on hand when equities become cheap is a great buying opportunity for anyone that has cash available.

The challenge with having cash in hand is that while you have cash on hand, it’s not earning much of a return. It may not be as volatile as equities, but as I will get into later in this article, over the long-run, it’s better to have cash invested than not invested if your goal is to generate decent returns over the long run.

To have or not to have cash in your portfolio

Having cash as part of your portfolio will dampen the volatility of the overall portfolio but will also diminish returns when asset prices are rising. These results are indicative of an investor’s needs to decide on the level of cash in their portfolio should be based on their investment objectives and risk tolerance. An investor with a long-term horizon looking to maximize returns would likely benefit from having very little cash in the portfolio even if it comes with higher volatility. While a retiree that is withdrawing funds from the portfolio to cover periodic expenses might prefer to have a higher level of cash to reduce volatility and have access to that cash without having to sell at inopportune times.

The long-term investor with too much cash on hand, however, poses another risk. That is, the difficulty of market-timing and how being in the market even during the 10 worst days is better than being out of the market on the 10 best days. Studies have shown that investors that remain fully invested over the long-term – even during market downturns – have considerably higher returns than investors that remain on the sidelines as markets recover.

On the other hand, I don’t know of any studies that have confirmed that timing the market is a fruitful strategy, save for a few investors that we may never have heard of. Someone might have timed the market right on an occasion or two, but to time it right enough to outperform a buy and hold strategy – practically impossible for mere mortals.

So if you don’t have cash on hand how in the world are you supposed to buy the dips that present such great buying opportunities? Investors always say, I’m buying the dip. That’s great, but you probably missed the run up by holding cash for the entire time preceding the dip!

Unless of course you suddenly came into a lot of money. If so, congratulations.

You may also have sold a position – hopefully at a gain – and were looking for the next opportunity. But if you’re fully invested, it’s likely there won’t be more than 2-3% available at a time to invest when the market does pull back, which means 97% of the portfolio is exposed to the pullback. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing because again, it’s better to be in the market than out of the market.

A Look at the Impact of Cash on Portfolio Risk and Returns

There are several occasions when having some cash on hand is a tactically smart approach – most notably when funds are being pulled out of the account regularly such as what occurs in retirement. Having some cash on hand limits having to sell positions to meet monthly cash flow needs. If 4% of the portfolio is needed annually, it might be good to have around 3-4% in cash so there is less need to sell to cover the periodic expenses. Presumably, the portfolio will be generating enough in returns to replenish that cash on an ongoing basis, either through income-generating securities or tactical selling throughout the year – which could help to manage tax liabilities if the funds are invested through a taxable account.

To look at the impact on returns and volatility of cash in a portfolio, I took data returns for the S&P 500 going back to 1980. As a proxy for cash, I used a return of 0.5% annually, assuming that the cash is held in a money market account. You could argue that the cash portion could be held in a short-term Treasury, and that would change the overall returns and volatility, but for simplicity, I used money markets because they have little to no price fluctuations other than the ‘breaking the buck’ situation that occurred during the Great Recession.

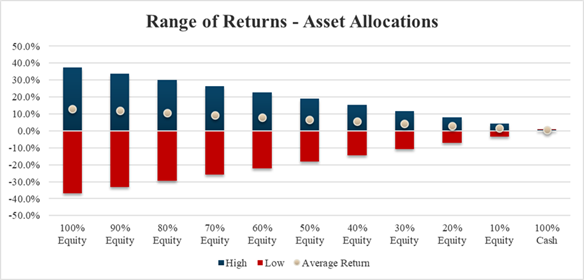

The results are as expected – the greater amount of cash in the portfolio, the lower the overall returns and the narrower the range of returns you will generate. As an investor, therefore, you would have to decide between higher returns and higher volatility, or lower returns and lower volatility.

Chart 1: Asset Allocation Range of Returns of Equities and Cash

Source: NFG Wealth Advisors

As the table below indicates, a portfolio with 100% in the S&P 500 would have had an annualized return of 11.8% with a standard deviation of 16.5%. While a portfolio with just 10% in equity and 90% in cash would have had an annualized return of 1.7% with a standard deviation of 1.7%. ( I did not use the 100% cash portfolio because when returns are the same every year, the standard deviation is zero and the return/risk metric gives an error.) The question then is a matter of whether the returns being generated with a considerable amount of cash in the portfolio is worth the lower volatility.

One might argue that the amount of return might not be worth the additional risk by looking at the return/risk metric, which indicates that as cash increases, so does the risk-adjusted return as measured by the return/risk metric. For a 100% equity portfolio, the return/risk is 0.71, whereas a portfolio with 90% in cash has a return/risk of 1.06. Choosing where to focus along the spectrum then, is a choice between how much return you would like to generate versus how much risk you are willing to take – knowing that risk-adjusted returns diminish as cash is reduced.

Table 1: Asset Allocation Ranges between 100% Equity and 100% Cash

Source: NFG Wealth Advisors LLC

Comparing these returns to a portfolio that invests in fixed income instead of cash provides some interesting insights (see table below). For the fixed income portion, I used the iShares Barclays Aggregate Bond Index ETF (AGG). Returns using fixed income are higher across the entire spectrum regardless of the split between equities and fixed income, but let’s look at some specific comparisons.

Going back to our original analysis using equities and cash, a portfolio with 60% in equities and 40% in cash had an annualized return of 7.6% and a standard deviation of 9.9%. In order to generate a comparable return using fixed income instead of cash, we can look at two ways of implementing it. We can target an allocation that provides a similar expected return with less risk, or an allocation with similar risk that provides a higher expected return.

Table 2: Asset Allocation Ranges between 100% Equity and 100% Fixed Income

Source: NFG Wealth Advisors LLC

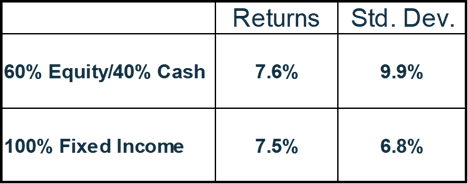

For the former, we see below that a portfolio of 100% fixed income generated an annualized return of 7.5% with a 6.8% standard deviation. A similar return to the cash portfolio but with 30% less volatility.

Table 3: Comparison of Portfolios with Similar Returns

Source: NFG Wealth Advisors LLC

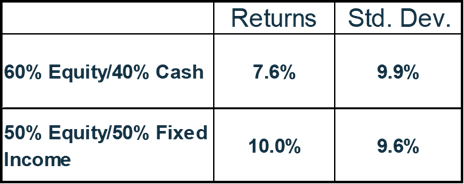

If we try to match the volatility of our 60/40 cash portfolio instead, we also see that a portfolio made up of 50% equity and 50% fixed income provided an annualized return of 10% with a standard deviation of 9.6%. This time the portfolio has similar volatility, but the returns were 33% higher.

Table 4: Comparison of Portfolios with Similar Standard Deviation

Source: NFG Wealth Advisors LLC

I would also point out that the risk-adjusted returns, as measured by return/risk, are all higher in the portfolios using fixed income and with no more than 40% in equities. In fact, the allocation with the highest risk-adjusted return is 20% equity and 80% fixed income with a return/risk metric of 1.24.

Conclusion

So is cash really king or is there a better alternative to optimizing portfolio returns? We go back to the question about investment objectives and risk tolerance of each individual investor. An investor drawing funds from their portfolio should have some level of cash in order to facilitate the withdrawal of funds, particularly when faced with inopportune times to sell assets, such as when the market declines. However, it seems that having too much cash is a big drag on returns when prudent alternative asset allocations will do just fine – particularly well-diversified strategies that include multiple asset classes such as equities and fixed income.

As for cash in the investment portfolio, one approach I take with clients is for them not to consider cash as part of their investment portfolio. If I’m managing your investments, I don’t need to have cash unless it has been earmarked for deployment. In which case, we will likely deploy it as soon as we identify how it should be invested within the context of the investment strategy and the current holdings in the portfolio. So as far as we are concerned, cash is not king when it comes to investing.